By Paul J. Knight, Jenny Lisignoli, and Mikaela Buscher

Since the passage of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1973, national awareness has focused on the fate of plant and animal species threatened with extinction. The salvation

of the once endangered bald eagle lent credence to the importance of the ESA, imbedding it firmly in the consciousness of the nation. In 1963, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) reported only 417 nesting pairs of bald eagles in the lower 48 states (Photograph 1). In 2021, more than 71,400 pairs were documented (USFWS 2021).

It is important to note that biological surveys are required for environmentally related projects that may potentially affect these federally listed threatened and endangered species protected under the ESA. But people may not realize that because of a separate law, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) nearly every biological survey NV5 biologists conduct to clear a project also requires a migratory bird nest survey.

Although many Americans may be aware of the MBTA, few may understand its significance and what it does. The MBTA was passed in 1918, fifty-five years before the ESA. The ESA addresses a select group of threatened or endangered species based on data collected by experts in the scientific community, whereas the MBTA provides substantial protection to every migrating bird species across the United States. Without this Act, many of the bird species we see every day might disappear.

As of 2020, 1,093 species of birds were included on the MBTA list (USFWS 2020). These species vary from the small Calliope Hummingbird, which weighs only 0.1 ounce and would fit in the palm of your hand (North American Nature 2022a), to much larger birds, such as the Trumpeter Swan, which has a wingspan of 6.5 feet and can weigh up to 30 pounds (North American Nature 2022b). The MBTA has strict guidelines regulating project activities at active nest sites that prohibit the taking, killing, capturing, selling, trading, and transport of protected migratory bird species, without specific authorization and permits obtained from the USFWS (USFWS 2021). This Act not only includes protection of adult birds but also their eggs and active nest sites (USFWS 2021).

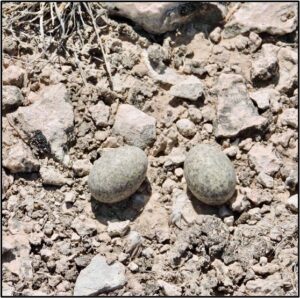

Bird nests come in many sizes and shapes and can vary dramatically in how they are constructed. For example, they can include traditional cup nests made of grass and twigs (Photograph 2), eggs laid on open ground, or in a slight depression (Photograph 3), and nests created with mud and found in colonial settings (Photograph 4). When planning migratory bird nest surveys NV5 biologists must consider not only what time of year the birds will be nesting, but also be aware of the types of nests they may encounter.

Migratory birds are common across the nation from the highest mountain peaks to the lowest deserts, often fluttering just outside of your windows or flying across parking lots. Since birds are found across the country, why was the MBTA even passed in 1918? At that time commercial-scale hunting was largely focused on meeting a growing demand for feathers that adorned women’s hats. State laws then were incapable of controlling the hunting for such feather demands, and many bird populations were devastated (MSU 2022). By the early 20th century, species such as the Carolina Parakeet, Great Auk, Labrador Duck, as well as the now famous Passenger Pigeon were extinct. In 1833, John James Audubon reported the Passenger Pigeon was the most numerous bird species on the continent. He observed that a single flock of Passenger Pigeons passed over his head and blocked the sun for three days (Scientific American 2014). On September 1, 1914, barely 80 years after Audubon’s observation, the last known Passenger Pigeon, a female named Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo (Audubon 2014). Thankfully however in 1918, due to a growing concern that if something was not done soon, many North American birds would disappear forever, the US Congress passed the MBTA.

Originally the MBTA implemented a treaty between the United States and Canada (then part of Great Britain), but the scope of this Act has since widened, as additional treaties with Mexico, Japan, and Russia have also been signed (USFWS 2020). Quietly, and unbeknownst to much of the U.S. population, this act for more than a century has provided protection to nearly every native bird species in the United States. Because of this Act, you can still look out your window and see a bird searching your lawn for bugs, or awaken to their songs at sun rise.

Citations

USFWS (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). 2021. “Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucoephalus) Fact Sheet”. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/bald-eagle-fact-sheet.pdf.

USFWS. 2020. Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. https://www.fws.gov/law/migratory-bird-treaty-act-1918.

North American Nature. 2022a. 10 Smallest Birds in North America. Article available at: https://northamericannature.com/10-smallest-birds-in-north-america.

North American Nature. 2022b. 11 Largest Birds in North America. https://northamericannature.com/10-smallest-birds-in-north-america.

Michigan State University Animal Legal and Historical Center (MSU). 2022. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act. A Brief Summary of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA). Written by K. Rozan.

Article available at: https://www.animallaw.info/article/brief-summary-migratory-bird-treaty-act.

Scientific American. 2014. 3 Billion to Zero: What happened to the Passenger Pigeon? Written by D. Biello. Article available at:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/3-billion-to-zero-what-happened-to-the-passenger-pigeon.

Audubon. 2014. Why the Passenger Pigeon Went Extinct. Audubon Magazine May-June 2014.

Written by B. Yeoman. Available at: https://www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june-2014/why-passenger-pigeon-went-extinct.

Please note: Photographs 1-4 by Paul Knight and Photograph 5 from Wikipedia – Martha (Passenger pigeon) available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martha_%28passenger_pigeon%29.